The Physiology of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation

Highlights

- With current strategies, compressions and ventilations can generate a cardiac output equivalent to 15-25% of normal output (View Highlight)

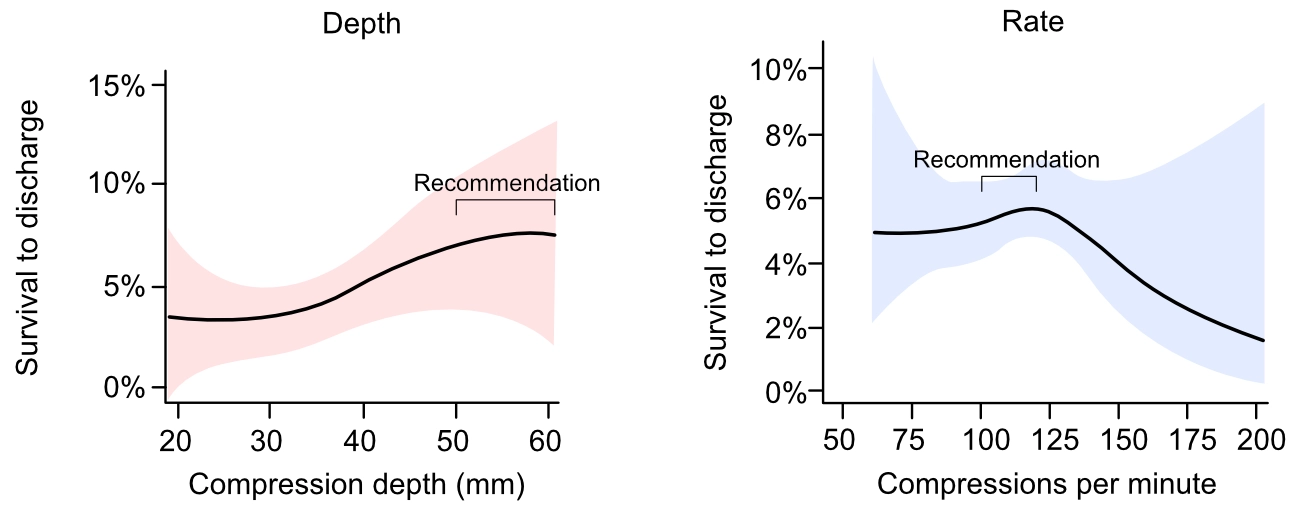

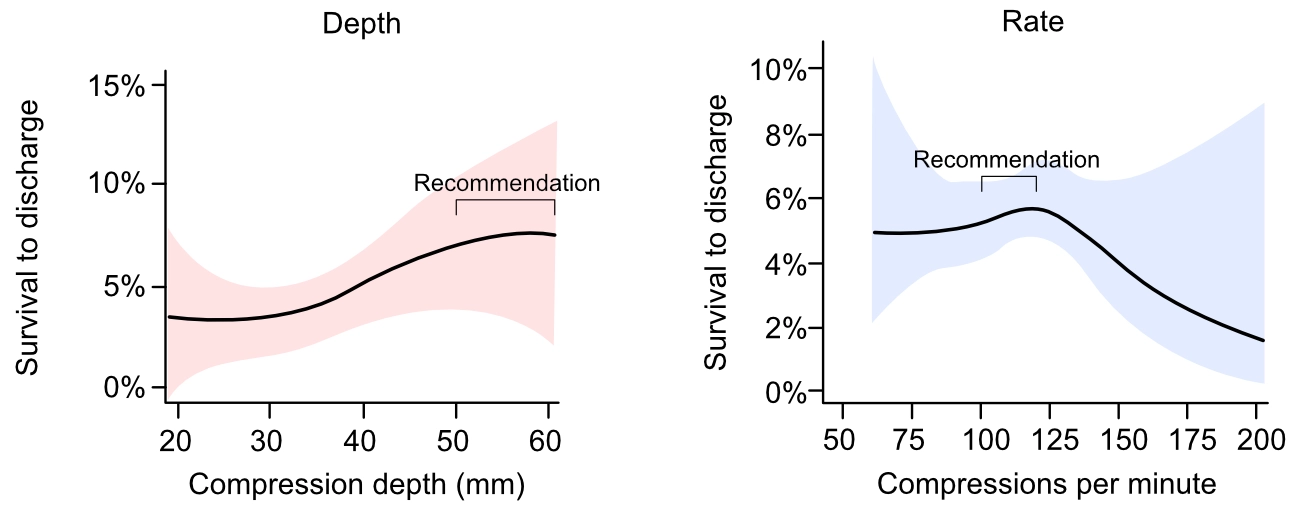

- Current guidelines recommend a compression depth of 5–6 cm at a rate of 100–120 compressions per minute (Figure 1). These recommendations are based on observational data (Stiell et al, Idris et al). Randomized clinical trials are lacking.

(View Highlight)

(View Highlight)

- The VF waveform is initially coarse (i.e fibrillatory waves have large amplitudes) but as the duration of VF is prolonged, the amplitude gradually diminishes and fine VF (small fibrillatory amplitudes) ultimately degenerate into asystole (View Highlight)

- The gradual progression from coarse VF to fine VF and finally asystole is the result of diminishing ATP concentration in the myocardium. ATP depletion results in cellular dysfunction and renders the defibrillation ineffective (View Highlight)

- In circumstances with non-shockable rhythm or with prolonged periods of VF (fine VF resistant to defibrillations), the purpose of CPR is to induce myocardial electrical activity by generating adequate coronary perfusion pressure (CPP (View Highlight)

- Studies demonstrate that a coronary perfusion pressure (CPP) of 15 mmHg is required in order to induce electrical activity in the myocardium (View Highlight)

- The coronary perfusion pressure (CPP) can be calculated as follows:

CPP = Paorta – RAP

Paorta is the intra-aortic pressure (where the coronary arteries originate)

RAP is right atrial pressure (where venous coronary blood is emptied) (View Highlight)

- CPP is approximately 0 mmHg (i.e there is no coronary blood flow) during the compression phase, which is explained by the fact that the pressure is equally elevated in the aorta and the right atrium (View Highlight)

- The decrease in right atrial pressure and ventricular pressure is also important because it allows for passive flow of blood to the atria and ventricles (View Highlight)

- al).

Figure 6. Coronary perfusion pressure (CPP) during CPR (View Highlight)

- CPP is very sensitive to interruptions in the compressions. Brief interruptions (seconds) abolishes the CPP completely and it takes around15 compressions to re-establish the CPP after an interruption (View Highlight)

- The compressions also lead to increased pressure in the veins in the thorax (paravertebral veins, epidural veins) and the spinal fluid. Unfortunately, this increase in pressure is propagated to the brain and leads to an increase in venous cerebral pressure, and subsequently increased intracranial pressure (ICP). High ICP counteracts the cerebral perfusion pressure (CerPP). (View Highlight)

- Ventilation is less critical during the first 4–5 minutes (View Highlight)

- positive pressure ventilation is recommended as soon as possible because the effectiveness of the compressions diminishes after a few minutes of compressions. This is explained by the fact that the pulmonary vessels and bronchioles collapse gradually during the compression phase (Dunnham-Snary et al). To expand the pulmonary vessels and bronchioles, positive pressure ventilation must be performed (View Highlight)

- Hyperventilation must always be avoided during cardiopulmonary resuscitation. It prevents the pressure drop in the thorax, which counteracts the passive filling. Hyperventilation also leads to increased right atrial pressure during diastole, which reduces CPP. In an animal study, CPP decreased by 28% during hyperventilation (View Highlight)

(View Highlight)

(View Highlight)